The Role of Temperament in Personal Image

The Subconscious Impact of Temperament

Our inherent temperament—that unique blend of genetic predisposition and early experiences—subtly shapes how others perceive us from the very first moment. This invisible force manifests through our body language, speech patterns, and emotional responses, creating immediate judgments that often occur below conscious awareness. Research shows these snap judgments form within 100 milliseconds of meeting someone, highlighting temperament's powerful role in social dynamics.

Consider how two colleagues might enter a meeting: Sarah immediately engages others with animated conversation, while David prefers observing quietly before contributing. Neither approach is inherently better, yet each creates distinct impressions. These temperament-driven behaviors become the lens through which others interpret our competence, warmth, and trustworthiness, often before we've spoken a complete sentence.

Early Experiences and Temperament Formation

The foundation of temperament emerges from a complex interplay between biology and environment. Studies of identical twins reared apart reveal striking similarities in temperament, suggesting strong genetic components. Yet equally compelling is the work of developmental psychologists showing how early caregiving experiences can modify these innate tendencies.

Imagine two children with similar biological predispositions: one raised in a nurturing, responsive environment develops confidence exploring new situations, while another facing inconsistent care might become more cautious. These early imprints don't determine destiny, but they create default patterns that influence our social interactions throughout life—patterns we can learn to recognize and adapt when needed.

The Role of Temperament in First Impressions

First encounters act like temperament Rorschach tests—we unconsciously project our own temperamental biases onto others. An extroverted manager might misinterpret an employee's quiet reflection as disengagement, while an introverted teacher could mistake a student's enthusiasm for disruption. These misreadings often stem from assuming others experience the world exactly as we do.

The most effective communicators develop what psychologists call temperament literacy—the ability to read and adapt to different behavioral styles. This might mean giving space to process thoughts for reflective types or providing immediate feedback for those who thrive on interaction. True connection happens when we meet people where they are temperamentally, rather than expecting them to conform to our preferences.

Extroversion and Introversion: Communicating Through Energy Levels

Understanding Energy Levels

The extroversion-introversion spectrum represents one of psychology's most well-documented temperament dimensions, yet remains frequently misunderstood. Contrary to popular belief, these categories don't describe social skill but rather how people recharge their mental batteries. Extroverts literally derive cognitive energy from external stimulation, showing increased brain activity in response to social interaction, while introverts' neural pathways require downtime to restore focus.

Modern workplaces often privilege extroverted norms—open offices, constant collaboration, rapid-fire meetings. Yet research by Susan Cain and others reveals that many groundbreaking ideas emerge from solitary reflection. The most innovative teams balance both energy styles, creating spaces for spontaneous brainstorming and quiet deep work.

The Impact of Energy on Communication Styles

Communication differences between energy types often cause unnecessary friction. Extroverts process thoughts verbally, thinking by speaking, while introverts typically think before speaking. This explains why meetings often feel unbalanced—the fastest talkers aren't necessarily the most insightful, just the most comfortable thinking aloud.

Tech companies like Microsoft have addressed this by implementing think time before discussions, allowing all temperaments to contribute meaningfully. Similarly, some educators alternate between group work and independent study to honor different learning styles. When we structure interactions to accommodate various energy needs, we access the full range of human intelligence.

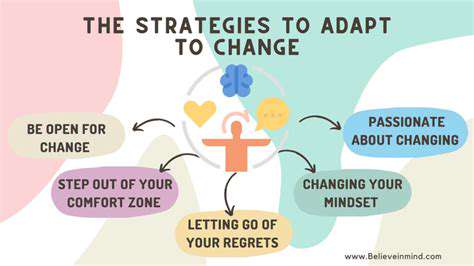

Strategies for Cross-Temperament Communication

Bridging energy differences requires intentional practices. For extroverts: practice active listening without interrupting, ask open-ended questions, and respect processing time. For introverts: prepare talking points in advance, schedule energy-replenishing breaks, and practice concise contributions. The magic happens when we view temperament differences as complementary rather than conflicting.

Consider how some of history's most effective partnerships paired contrasting temperaments—Steve Jobs' visionary enthusiasm balanced by Steve Wozniak's quiet technical genius. Great teams aren't uniform; they're symphonies of different but complementary temperaments working toward shared goals.

Adapting Your Image: Leveraging Temperament for Success

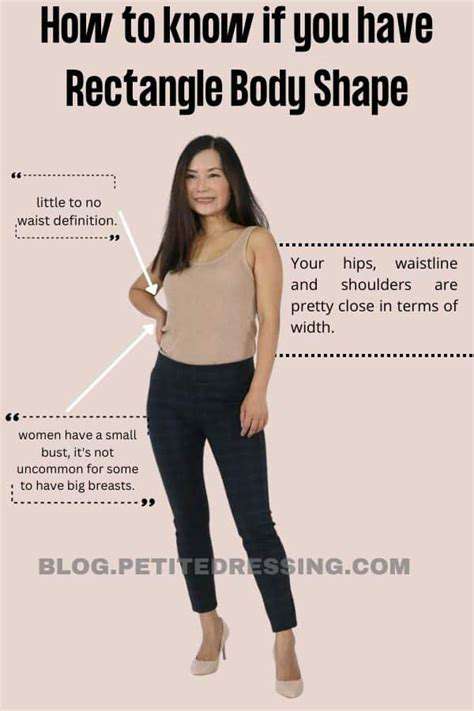

Authentic Adaptation vs. Performance

Successful image adaptation isn't about pretending to be someone else—it's about strategically emphasizing different aspects of your authentic temperament for specific contexts. A naturally reserved lawyer might cultivate precise, powerful speech patterns for courtroom appearances, then return to more reflective communication with colleagues.

The key lies in what psychologists call self-monitoring—the healthy ability to adjust behavior appropriately to social contexts without losing core identity. High self-monitors report greater career success and life satisfaction, as they navigate diverse situations with emotional intelligence.

Temperament-Aware Personal Branding

Your professional image should reflect your genuine strengths while accommodating audience expectations. An introverted financial advisor might emphasize their thoughtful, analytical approach rather than trying to mimic extroverted sales tactics. Clients increasingly value authenticity over performative enthusiasm in many professional contexts.

Digital communication offers particular advantages for various temperaments. Introverts often excel in written mediums where they can carefully craft messages, while extroverts might leverage video content to showcase their natural energy. The most effective personal brands play to temperamental strengths rather than fight against them.

The Neuroscience of First Impressions

Recent fMRI studies reveal that first impressions activate ancient brain regions associated with threat assessment. Within seconds, others' brains are deciding: friend or foe? safe or dangerous? This explains why temperament cues like calm demeanor or confident posture carry disproportionate weight.

By understanding these primal processes, we can craft presence that puts others at ease. Simple practices like mindful breathing before important meetings or power posing in private can help regulate the physiological signals our temperament broadcasts.

Read more about The Role of Temperament in Personal Image

Hot Recommendations

- Grooming Tips for Your Bag and Wallet

- Best Base Coats for Nail Longevity

- How to Treat Perioral Dermatitis Naturally

- How to Use Hair Rollers for Volume

- How to Do a Graphic Eyeliner Look

- Best DIY Face Masks for Oily Skin

- Guide to Styling 4C Hair

- Guide to Improving Your Active Listening Skills

- How to Fix Cakey Foundation

- Best Eye Creams for Wrinkles

![What to Wear on a Plane [Comfortable & Stylish]](/static/images/29/2025-05/ChooseFabricsWiselyforMaximumComfort.jpg)

![How to Do a Red Lip Look [Classic & Bold]](/static/images/29/2025-05/MasteringtheClassicRedLip3AATimelessChoice.jpg)

![Review: [Specific Sock Brand] Fun Designs](/static/images/29/2025-05/SizingandFitConsiderations.jpg)

![Review: [Specific Brand] Swimwear Collection](/static/images/29/2025-05/StyleVarietyandDesignElements.jpg)